A Cautionary Tale involving a Routine Knee Replacement and Infection Control

For Ben, the operation couldn’t come soon enough. He’d struggled for 15 years with a damaged knee after he was stretchered off the soccer pitch after a bad tackle. The doctors said he would never fully recover, and they were right. They also said he could need his kneecap replaced eventually and they were right about that too. The day had finally arrived. Ben was going into hospital for his knee replacement operation.

Ben’s total knee replacement operation went well, taking around 3 hours under general anaesthetic

The surgeon cut down the front of Ben’s knee to expose the kneecap. The surgeon then moved to the side so they could get to the knee joint behind it. The damaged ends of the thigh bone and shin bone were cut away. The ends were precisely measured and shaped to fit the prosthetic replacement. The end of Ben’s thigh bone was replaced by a curved piece of metal, and the end of his shin bone was replaced by a flat metal plate. A plastic spacer was placed between the pieces of metal, to act like cartilage. The wound was then closed with either stitches or clips and a dressing is applied to the wound.

Once Ben had recovered from the anaesthetic he was taken back to the surgical ward to start his recovery which started well. Ben spent the first day resting. He was given pain killers, monitored by the nursing staff and had his dressing changed. After a day in bed, physiotherapists came to see him. They got him walking with a frame and showed him some exercises he could do straight away to strengthen his knee. Everything was going well!!!

When Ben woke up the next morning he didn’t feel well

His knee was sore and his leg below the dressing was red and swollen. By the time nursing staff came to see him, he was feeling dizzy and hot. The staff found he had a temperature, concluded he had an infection and gave him i.v. antibiotics. The hospital had screened Ben for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) when he came into hospital, but the results hadn’t come back from the lab. Nursing staff continued to monitor Ben for several hours, but he showed no signs of improvement. Eventually, his MRSA screening came back, and he had tested positive. Ben’s antibiotic was switched, and he was moved into another ward joining other patients who were recovering from an MRSA infection.

Ben slowly recovered from his infection in the following days. He was able to resume his recovery from the operation. Although the MRSA infection had delayed his discharge by several days, Ben finally left hospital to continue his recovery at home.

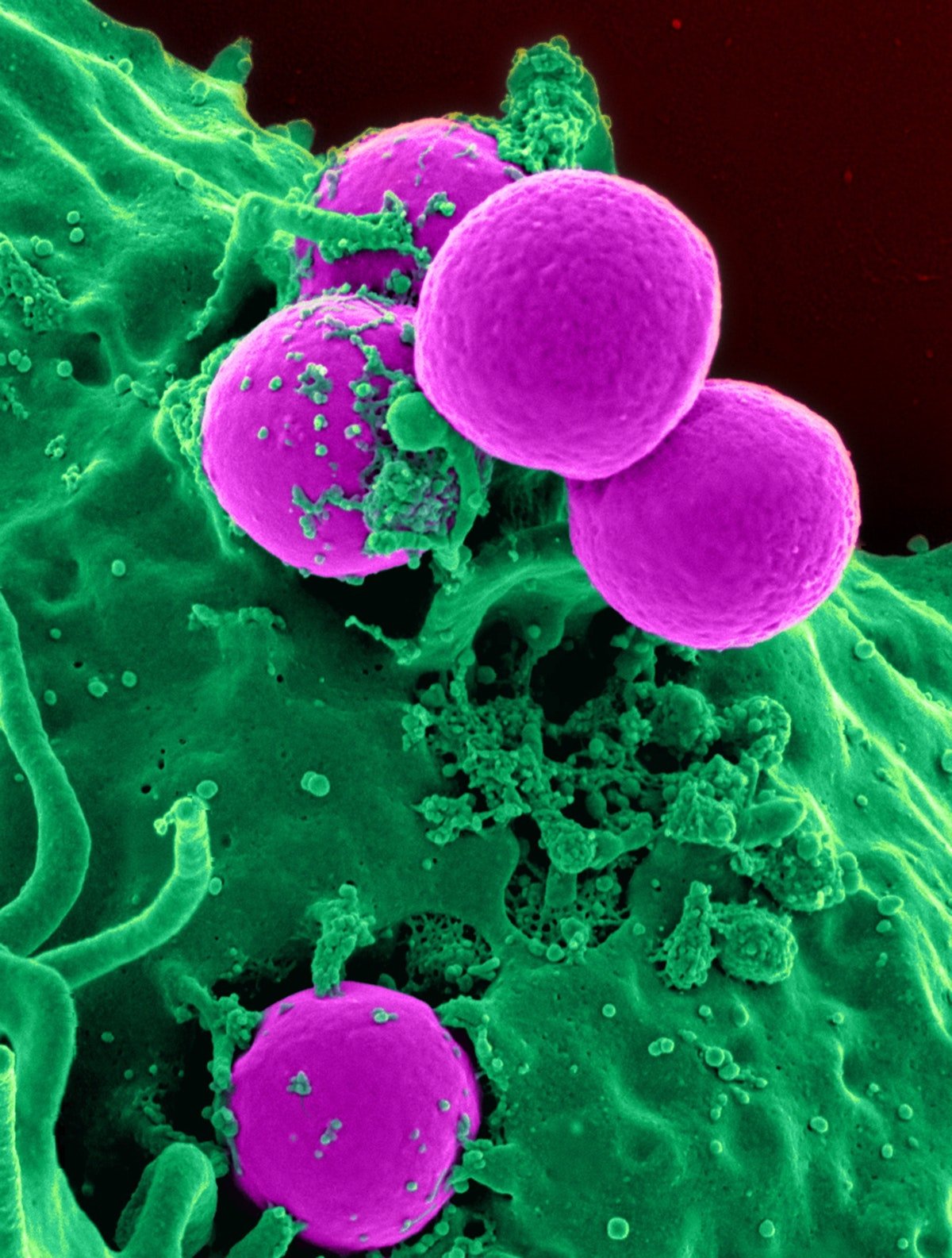

MRSA is a type of bacteria that's resistant to several widely used antibiotics

This means infections with MRSA can be harder to treat than other bacterial infections. MRSA is also one of a group of infections known as hospital acquired infections (HAI) or healthcare associated infections. It is an infection whose development is favoured by a hospital environment. These infections are usually acquired after hospitalisation and manifest themselves 48 hours after admission to the hospital. Around 5% of patients in hospital will pick up a HAI. The six most common types of healthcare associated infections, which account for more than 80% of all healthcare-associated infections are:

Pneumonia and other respiratory infections,

Urinary tract infections,

Surgical site infections,

Clinical sepsis,

Gastrointestinal infections, and

Bloodstream infections.

The main culprits associated with HAI are Clostridium Difficile causing infective diarrhoea, Staphylococcus aureus causing blood infections, urinary tract infections, surgical site infections like Ben’s and hospital acquired pneumonia which is the most common healthcare-associated infection contributing to death, Klebsiella which is associated with catheter induced urinary tract infections and surgical site infections as well as hospital acquired pneumonia and ventilator acquired pneumonia particularly in children. Escherichia coli is associated with surgical infections, hospital acquired pneumonia and ventilator acquired pneumonia in children and bloodstream infections. We must also acknowledge that today patients are also at risk of getting Covid 19 during their stay in hospital.

Hospital acquired infections are a real problem for hospitals and keeping them under control takes a lot of time, effort, and money

There is a huge amount of guidance available to ensure these infections are kept as low as possible. Some of this advice is pretty obvious and straight forward and some is a little more complex. Practices such as hand washing before patient contact, thorough cleaning of wards and surfaces and wearing PPE are all fairly obvious and should be a given in any healthcare facility. Others are less obvious but are just as important in helping to reduce hospital acquired infections. These include:

Screening patients such as preoperative patients for MRSA and then keeping those who test positive away from other patients, visitors and as many staff as possible.

Having national and local surveillance programs in place to monitor levels of healthcare associated infections.

Encouraging appropriate antibiotic usage. This reduces the risk of antibiotic resistance emerging which can lead to an increase in healthcare associated infections.

Developing, implementing, and maintaining guidelines that focus on infection prevention such as the World Health Organisation guideline on preventing surgical site infections.

Healthcare associated infections such as central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, surgical site infections, hospital-acquired/ventilator associated pneumonia and Covid19 infection continues to increase. These infections develop during the course of health care treatment and result in significant patient illnesses and deaths. They also prolong the duration of hospital stays; and necessitate additional diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, which generate added costs to those already incurred by the patient’s underlying disease. Healthcare facilities must do everything they can to bear down on hospital acquired infections. The outcomes for the patient will be better and ultimately the hospital will save money.

Simple things really work and help reduce hospital acquired infections

Hand washing, wearing appropriate PPE and using the right equipment are three simple ways to reduce the risk to patients. For example, to mitigate the risk of transmission of Covid19. stop using medical tape on your patient’s eyes in the operating theatre and ICU, removing a potential Covid19 transmission route and switch to sterile, single use EyePro™, the only sterile eyelid cover available.

Check out our short video below with our Medical Director, Andrew Wallis explaining the benefits of using EyePro.

Author: Niall Shannon, European Business Manager, Innovgas

This article is based on research and opinion available in the public domain.

Interested in a Free Sample?

Free samples of NoPress, EyePro & BiteMe available upon request.

Conditions apply.